On April 25, 2007, the Caribbean state of St Lucia, which in 1997 had established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China, switched sides and opened an embassy in Taiwan accredited to the Republic of China. The move was a result of what had been termed as “checkbook diplomacy,” namely the efforts by Taiwan to purchase diplomatic recognition with hard cash.

That much was acknowledged by St Lucia’s foreign minister, who unabashedly stated that his policy was to “support those who give you the most.”

After St Lucia’s move, Beijing went ballistic and denounced the endeavor as “brutal interference in China’s internal affairs.”

How the Caribbean’s poorest nation with barely 180,000 inhabitants could not only “interfere” but “brutally” so in the internal affairs of the longest continuous civilization in history with a population of around a billion is left to anyone’s imagination.

Ultimately for the two rival Chinas, the issue proved inconsequential. Taipei gained nothing and Beijing lost nothing. Conversely, Beijing’s reaction proved a harbinger of things to come.

New generation

One of Deng Xiaoping’s recommendations was that, in foreign affairs, China should “conceal one’s light and cultivate in the dark.” In practical terms this meant that China should observe calmly, hide its strength and bide its time with the understanding that it should only strike when warranted and when success was assured.

Underlying Deng’s vision was that of a China secure in its values, proud of its history and civilization and impervious to the petty barking of the barbarians at its gates. But it was not to last.

The advent of what can be termed the Xi Jinping regime saw not only the emergence of China as a major economic power but also the advent of a new generation among the country’s ruling bureaucracy. The changeover did not spare the foreign-policy establishment, where a new generation of diplomats slowly replaced their predecessors.

Most of these had been reared in pre-revolution days and many came from well-to-do, not to say Mandarin families whose ancestors had served the Empire with distinction.

Having benefited from a classical education, they were imbued with the grandeur of China’s civilization and, whatever the current state of their country, how it was perceived by the “barbarians” was the least of their concern. Overall, they ensured that China’s diplomatic corps stood out for its composure, professionalism and style.

Interacting with ‘barbarians’

The generational change in China’s leadership included a similar change among the diplomatic corps. The end result was that, in a relatively short number of years, a new ruling establishment found itself at the helm of a country that was now both a domestic heavyweight and a major player on the international chessboard.

This development, at the social level, ushered in a new era in the interaction between an increasingly large segment of China’s population and the outside world. Thus, while in 2000 some 9 million Chinese tourists traveled abroad, that number reached some 154 million in 2019. In that same year some 700,000 Chinese were studying abroad, half of them in the United States.

While it is difficult to quantify the effect of this movement on the country’s psyche, the concept of foreign “barbarians” gave way to a mixed perception in which “foreign” no longer automatically equated to something distant, not to say alien and incomprehensible; and it could also prove desirable, such as acquiring imported luxury goods or studying abroad.

For the Chinese establishment, managing its newfound power within the context of its ongoing interchange with the outside world proved a multifaceted challenge. This applied not only to how to project China’s military might or its economic clout in an international environment, but also how to manage the image of China abroad.

Part of this new challenge consisted of consolidating the image of the Chinese state as one that is concerned with the security and well-being of its citizens abroad, a concern that would reflect positively on the Communist Party and which became particularly relevant as the number of Chinese citizens abroad skyrocketed.

Thus, in 2011, as Libya sank into anarchy, the Chinese authorities successfully evacuated some 35,000 of their citizens who had been working in the country. In 2016, in collaboration with the Thai and Laotian police, a Chinese unit rescued a number of Chinese crew members abducted by pirates on the Mekong.

Rise of the Wolf Warriors

While both these two operations met with considerable domestic applause at the grassroots level, they should be seen as a component of a much wider foreign-policy vision, namely Major Power Diplomacy.

MPD emerged from 2013 onward, as the expression of China’s diplomatic role in the global arena as seen from the perspective of the Xi Jinping regime; or, in other words, how to position China diplomatically in an international environment.

While the concept of MPD was in essence a theoretical one, its implementation took the world, and in particular the West, by surprise.

Practically overnight, under the label of Wolf Warrior Diplomacy, any foreign expression that was perceived as a criticism of China, be it in the media, in the cultural world or by political figures, was met with a a barrage of denunciation of colossal proportions emanating from China’s diplomatic missions abroad.

Thus in 2019, after the awarding of a Nobel Peace Prize to a Chinese dissident, the Chinese Embassy in Stockholm became embroiled in a vociferous exchange with both the media and the political establishment.

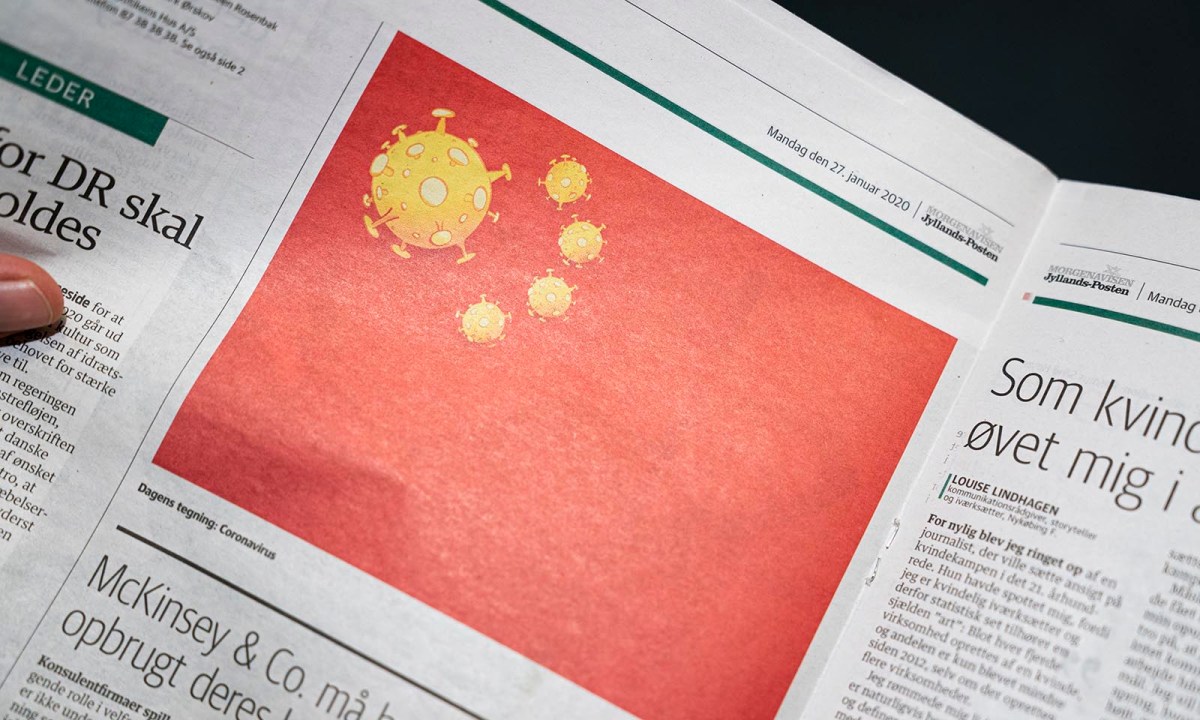

In January 2020 a Danish broadsheet, the Jyllands-Posten, published a satirical cartoon in which the five stars of the Chinese flag had been replaced by five coronaviruses. The cartoon would have gone unnoticed had not the Chinese Embassy in Copenhagen gone ballistic.

Not only did the embassy decry the cartoon as an “insult to China,” but the ambassador personally demanded an apology from the newspaper’s editor. That such an apology, in a country where freedom of expression is ingrained in its culture, was not in the cards was a given.

Somewhat similar confrontations between Chinese embassies and local entities, be it the media, non-governmental organizations or even the authorities, occurred in the UK, in France and even in staid Switzerland. With communications being what they are, China’s reactions became front-page news even in countries not directly concerned.

What emerged from this deluge of protestations was, seen from a Western perspective, a China that was unsure of itself, could not put up with any form of criticism, and appeared to verge on the ridiculous.

In a Western environment where criticism is the rule, derision a daily occurrence and dissent ingrained, China’s barrage of protestations rapidly bore fruit, although not necessarily what the Chinese authorities might have expected.

In October 2020 it emerged from a Pew Research survey that 78% of Western Europe’s population had developed a negative view of China. And while by 2021 it appeared that China was endeavoring to recalibrate its vision of how it should address foreign criticism, the damage had been done.

Not only had China’s “soft power” been wiped off the map but the damage done to China’s image in the industrialized world was such that it would take years to repair.

While in terms of promoting China’s international image Beijing’s reaction proved an unqualified disaster, in terms of substance it proved inconsequential. Neither China’s economy, not its industrial base, nor its military potential were in any way affected. Conversly, it raised a number of concerns regarding both the inner workings of the Chinese system and China’s perception of the outside world.

One can presume that the decision to turn up the volume in terms of denouncing all foreign criticism of China, real or perceived, was made at a level higher than the Foreign Ministry. Why it was made is unclear, but if the purpose was to silence China’s critics, it was so obviously bound to fail that one can wonder how much thinking preceded its implementation. And this in turn raises another question.

There is in China today a reservoir of knowledge and understanding on how Western societies function. Likewise, there is no dearth of international public relations firms that will design strategies to manipulate public opinion.

Clearly, if either or both of these resources had been tapped, the world would not have seen the ambassador of the second-largest economy getting involved in an absurd spat with the editor of an insignificant Danish newspaper. Which in turn raises another matter: feedback.

Lost in translation

Having received his instruction from his capital, it is indeed a courageous Chinese diplomat who would report to his hierarchy that Wolf Warrior Diplomacy is actually counterproductive and does not interface with a Western social environment, a contention that probably could be applied to China’s overall communication strategy to the outside world.

To wit, a Swiss newspaper recently published an opinion piece, signed by the Chinese ambassador in Bern, illustrating the achievements of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of China.

The piece was visibly first drafted in Chinese either in Beijing or in Bern, then cleared by Beijing and subsequently translated into French. While the translation was grammatically correct, the end result was a text that a Chinese person would have understood but which was totally incomprehensible for the average Swiss reader.

Actually, what the original text would have needed was not only a translation but some very substantive editing, not a likely endeavor in the current political climate. The end result was that the Chinese Embassy in Bern could claim that it had successfully placed an opinion piece in a major Swiss newspaper, while the impact of the piece could be quantified as zero.

It will take years, if ever, for China’s international image to recover from the spasms generated by Wolf Warrior Diplomacy. This would not necessarily have been so had the system been geared to leave a door open to negative feedback regarding political decisions made at the top of the hierarchy, feedback that would have permitted the regime a speedy change of course.

However, this in turn would have meant tolerating and managing a degree of dissent that the system does not seem willing or able to co-exist with.

Having lifted a rock only to drop it one one’s feet, the best one can hope for China is that, given its ideological options, the regime will realize that communicating with the outside world is not something it is programmed to excel in.

In a long-term perspective, Wolf Warrior Diplomacy will be seen as a hiccup of little practical consequence. Conversely, that it ever occurred and that it was not corrected in time should be, for the regime, cause for concern.