At a time when statues representing histories of slavery, racism and colonialism are being toppled across the United States and worldwide, Japan is moving in the opposite direction.

It has – this very month – opened a new historical center that completely ignores historical crimes. These crimes are widely known: The mobilization of countless Chinese, Koreans and Allied prisoners of war to work as forced labor during World War II.

It’s a shame. The opening of Japan’s industrial heritage center in mid-June should have been cause for celebration, for it details how the country created an industrial base – the first Asian nation to do so and a global benchmark for modernization.

Instead, it demonstrates that Tokyo is attempting to whitewash its aggressions in the first half of the 20th century. And remarkably, this whitewash negates promises made to a major UN body.

Meiji and UNESCO

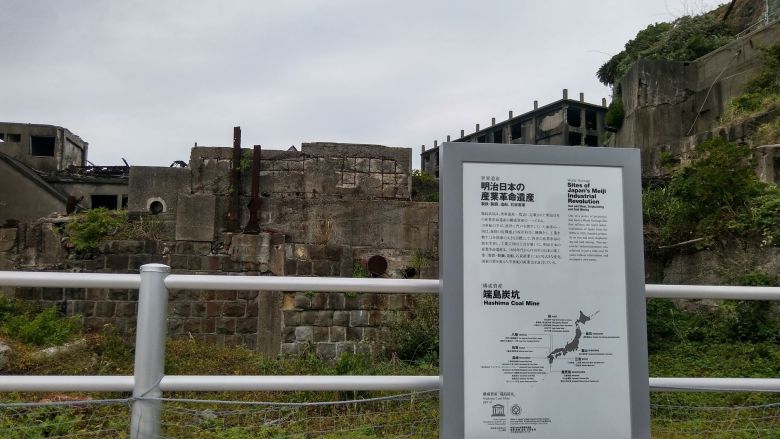

On July 5, 2015, 23 sites of Japan’s Meiji Industrial Revolution related to iron, steel, shipbuilding and coal mining were designated World Heritage Sites by the World Heritage Committee (WHC) of UNESCO.

At the time, the WHC recommended that Japan prepare “an interpretive strategy” to enable a full understanding of the history of each site. Tokyo accepted this advice and pledged to take measures “to enable the understanding that a large number of Koreans and others were mobilized against their will and forced to work.”

What the Japanese government acknowledged at the time was hardly the fruit of new research. The material is, in fact, included in textbooks for elementary, middle and high school students in Japan.

In the five years since making its pledge, however, the Japanese government has reneged on its promise.

The dark side of development

Visitors to each of the 23 Meiji sites, when perusing informational signage, will learn that Japan borrowed the concept of industrial revolution from the West to lay the foundation for its modernization. The success of that strategy made Japan a beacon, for it was the first non-Western country to achieve world-class industrialization.

What visitors will not learn about is Japan’s mobilization of forced laborers during the Pacific War (1937-1945).

Nor will they learn that Japan’s industrialization enabled wars of aggression. Japan used shipbuilding technologies to create battleships, and leveraged its iron and steel-making know-how to make artillery. This power enabled Japan to colonize Korea and Taiwan; it subsequently used it to invade much of China and almost all of Southeast Asia before being defeated by the Allies in 1945.

During the war years, damage was colossal; millions died.

In 1955, the Japanese government released a prime minister’s statement apologizing for and reflecting upon Japan’s aggressions in the region. Incumbent Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has said he would carry on the statement.

But since the 23 Meiji industrial sites were designated UNESCO World Heritage sites, however, Japan has stealthily changed its attitude toward its recent history: from remorse over past wrongdoings to pride.

In mid-June, the Industrial Heritage Information Center opened. It’s exhibits show nothing about how Japan mobilized workers from Korea, China and other countries, as well as prisoners of war from Allied nations captured in Southeast Asia, and forced them to work at coal mines under harsh conditions and on near-starvation rations.

In fact, the center’s only related information is in testimonies related to Hashima Island – an iconic island that resembles a battleship, and was used as a location in the 007 film “Skyfall,” which was the site of coal mines during the war years – that deny any discrimination against non-Japanese workers.

Japan defies posterity

Yet, the facts related to forced labor are readily available. Not only are they included in Japanese school textbooks, but testimonies from witnesses have been published and victims have filed lawsuits against Japanese companies.

So why has Japan broken its word? In 2015, the WHC’s 21 member countries all paid careful attention to Japan’s attitude on this issue.

Five years later, however, they seem to have lost interest. Such indifference is what enabled Japan to shift its stance.

The UN was established in response to the devastation caused by the two world wars and to prevent recurrences. The UNESCO World Heritage system was set up to preserve heritage as common assets of humankind.

Because Japan’s industrial facilities are designated UNESCO World Heritage, they cannot become tools to beautify Japan’s history. Were this to be permitted, it would undermine UNESCO’s mission.

The history of Japan’s industrial heritage must be written in full, not in part. And if it is to be granted UNSECO status, it must be remembered collectively. If the Japanese government fails to keep its word, UNESCO must require it to do so.

That is the demand of history. But it is also the demand of the zeitgeist, which makes clear that the voices of historical victims must be heard, not ignored or erased.

Nam Sang-gu is chairman of the Institute for Korea-Japan Historical Issues at Seoul’s Northeast Asia History Foundation. He earned his Ph.D. from Japan’s Chiba University in 2005 for research into Japan’s remembrance of wartime victims.