So far no American ally has felt a need to react to the election debacles President Joe Biden suffered this week, notably in the state of Virginia, which his party controlled but then lost, and also in lesser votes elsewhere across the country.

Usually, there is no reason for, say, a German leader, to comment on a vote in a middle-sized American state. But in this case, cables sent out from foreign allies’ embassies in Washington will likely need to grapple with this question:

Is Biden already so wounded that, in just over three years, he’ll be replaced in 2024 elections and have his foreign policy initiatives overturned by a nationalistic populist in the image of Donald Trump or even by Trump himself?

His ratings in political surveys are as bad as Trump’s at their worst. Voters have begun to wonder if, with the spectacle of Biden’s occasional incoherent babbling, he is up to the job of the presidency.

Part of allied nations’ worry centers on the growing habit of US presidents to hang foreign initiatives on their own signature instead of gaining wider political consensus. In America’s volatile political landscape, this trend throws the staying power of US policy into doubt.

If a president believes he can’t get consent for a treaty from two-thirds of the US Senate, as constitutionally required, he forges ahead anyway and calls it something else.

For example, the Paris climate accord signed with dozens of other countries in 2015, was not labeled a treaty but an “executive agreement, binding only President Barack Obama’s administration,” wrote Anne-Marie Slaughter, a former diplomat who runs New America, a Washington think tank.

The same was true of Obama’s complex deal with Iran to curb its nuclear weapons program, known as the JCPOA. He called it a “non-binding agreement” that committed the US to lift sanctions on Iran if Tehran complied with a series on non-proliferation measures. “They can call it a banana, but it’s a treaty,” the late Senator John McCain complained at the time.

The weakness of each maneuver was evident when Trump took power after Obama. Because neither the Paris agreement nor the Iran deal was ratified in the Senate, Trump simply overturned each with the stroke of a pen.

This year, Biden has quickly reinstated Paris and wants to return to the Iran agreement. But what will happen after 2024?

America’s whiplash foreign policy presents uncertainty among US allies. “Pervasive gridlock, polarization and distrust that characterize our national politics will…give foreign leaders some pause before entering into long-term, costly agreements with us,” predicted William Howell, a University of Chicago political scientist.

“I think there is a real sort of underlying concern that America’s return may be temporary,” Max Bergmann, a fellow at the leftist Center for American Progress and specialist in relations with Europe. “Europeans are a little bit wary of following the lead of the United States.”

Biden insisted his election last year represented a clear return to US leadership in world affairs. At G-7 and NATO summits last summer, he announced—boasted, really– that “America is back.” Allies understood that he meant that the mercuric Trump and his “America First” attitudes had been pushed offstage. They publicly welcomed Biden with satisfaction.

But Western joy was tempered by an underlying fear that some version of Trump’s nationalistic populism, an ideology with a two-century history in the US, might in fact live on, analysts said.

“After Biden, it may be Trump again,” commented Gerard Araud, a former French ambassador to the United States. “We Europeans, we have to learn to be grown up, we have to learn to defend or to handle our interests by ourselves.”

Virginia’s election did not turn on foreign affairs but nonetheless showed American populism is alive and well.

The defeat of the state’s governor, deputy governor and attorney general were largely built on dissatisfaction among parents with school bureaucrats’ disdain for complaints about frameworks for teaching racial history and on efforts to give transgender students access to traditionally girl or boy bathrooms.

Nonetheless, by equating political control at home with an ability to lead the Free World, Biden set himself up for embarrassment.

Since taking office, he insisted the US must show the world democracy can work. On the eve of his trip to Europe last week, for a G20 summit and COP26 climate conference, Biden cajoled his own Democratic Party legislators in Congress to approve US$550 billion worth of programs to fight climate change. “The rest of the world wonders whether we can function,” he warned.

His chief Congressional ally, House leader Nancy Pelosi, said legislators must pass the spending measure so Biden wouldn’t be embarrassed when he got off his plane in Europe. But the legislators failed to endorse the package and Biden left Washington empty-handed.

US allies abroad had already been flummoxed by a series of Biden foreign policy missteps that made them wonder about his competence. NATO partners criticized Biden for the chaotic and incomplete evacuation of Americans, other foreigners and Afghan collaborators as Kabul fell to the Taliban.

He enraged France, America’s oldest ally, by quietly arranging a new anti-Chinese alliance with Britain and Australia, which denied Paris of a $100 billion submarine deal with Canberra. The secretive partnership also seemed a snub at continental Europe’s importance as a strategic partner.

“This brutal, unilateral and unpredictable decision reminds me a lot of what Mr Trump used to do. I am angry and bitter. This isn’t done between allies,” Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian said.

In the name of controlling climate change, Biden began to curb US fossil fuel production but, in order to keep American fuel prices low, he begged Russia and Saudi Arabia to produce more oil. Both refused.

Since January, tens of thousands of illegal immigrants have crossed the US southern border unhindered. Biden appointed Vice President Kamala Harris to solve the problem.

She traveled to Central America for talks about the flow, returned to declare the trip was a success “in terms of a pathway that is about progress” and didn’t take up the issue again. The migrants keep coming to the majority dismay of Americans.

In the Washington Post, a conservative Biden critic traced the beginnings of the president’s electoral problems in the US to the botched Afghan withdrawal. “After his Afghanistan debacle, the floor fell out from under the president,” the critic opined.

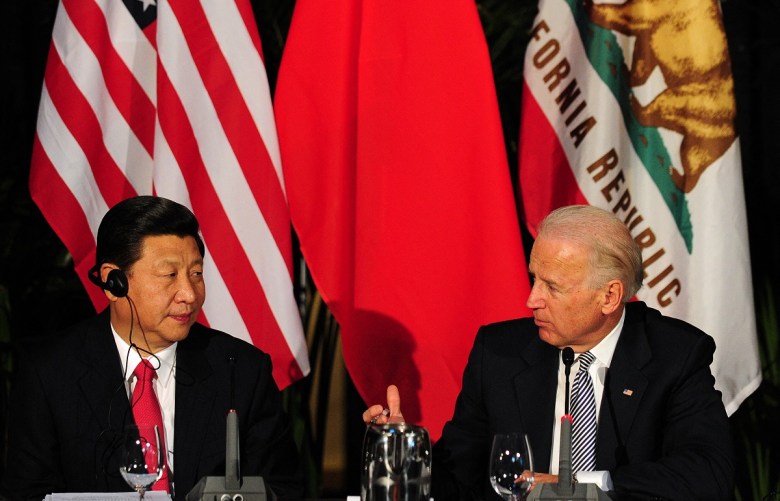

On the other side of the globe, it’s unclear whether China worries about Biden’s image problems at home. China is convinced the US is inexorably hostile, no matter who is president; US military leaders have labeled China a “pacing threat,” Pentagon language meaning it is on the military rise.

Bipartisan American criticism of China’s human rights record, US naval cruises through the contested South China Sea, which China considers its own, and support for democratic Taiwan’s separate status from China all convince Beijing the US won’t change course whoever might be elected in 2024.

A weakened US administration will likely embolden China to maintain, or even increase, pressure on Taiwan to negotiate about uniting with the mainland– though it appears Beijing hardly needs much encouragement.

China has held numerous military maneuvers around the self-governing island and staged jet bomber flights over its airspace, both as practice for a possible invasion and as psychological intimidation, regardless of Biden’s floundering at home or abroad.

To counter this, Biden hopes to renew dormant alliances in the Far East and add India to the mix. But potential partners will likely think twice about joining an anti-China coalition with a perpetually wavering and increasingly weak American administration.