While Asian cinema fans will be hoping that South Korean black comedy Parasite walks away with the greatest prize in film on Oscar night, many will also be hoping that another “Best Picture” nominee – Once up a Time in Hollywood – does not lift it.

Why so?

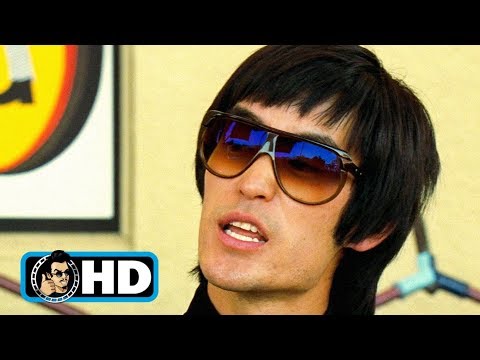

Because American auteur Quentin Tarantino’s ode to the twilight years of Hollywood’s golden age trashes the legacy of the greatest Asian film star of modern times: Bruce Lee. Tarantino’s portrayal of the late, great martial arts superstar as a cocksure and comical figure, who is unable to prevail in a fistfight with a fictional, white, all-American male played by Brad Pitt, has caused an uproar.

- The cause of the controversy: Bruce Lee, played by Korean-American actor Mike Moh, rumbles with Brad Pitt’s character in Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Video: YouTube

There have been commercial repercussions, too. The film, though pre-sold to China, was not shown in that lucrative market, reportedly over its portrayal of Lee.

The brouhaha comes at a time when many non-white Americans feel themselves on the defensive against what they consider a white backlash in Donald Trump-era America.

But what makes Lee so central a figure in popular culture and Asian representation?

Asia’s first superstar

Lee was born in 1940 to a theatrical family from Hong Kong, granting him early-age show business connections. A talented kung fu exponent, he traveled to the United States in 1959 for his university education, where he also taught martial arts.

His expertise in the then-exotic and secretive kung fu won him attention from competitors on the burgeoning US martial arts circuit. Though Lee did not compete, he won the respect of fighters including karate champion Chuck Norris, expanded his combative skills, and sculpted the sinewy physique that would soon become famous.

Brashly self-confident and charismatic, Lee gained attention in Hollywood and found himself coaching such figures as James Coburn and Sharon Tate.

His contacts won Lee cameos and a TV role as “Kato” the high-kicking sidekick to crime fighter The Green Hornet. Lee developed a script designed to grant him a starting role: As a renegade Shaolin monk wandering the American West. However, US producers did not believe Americans audiences were ready for a Chinese hero, and cast David Carradine in the role in Kung Fu.

Dismayed by racial prejudice, Lee returned to Hong Kong, where Shaw Brothers studios was churning out kung fu films. A new studio, Golden Harvest, offered Lee his breakthrough. In a series of movies, Lee exploded on screen, bringing hyper levels of personal charisma and physical skill to Hong Kong cinema.

In his first film, The Big Boss (1971) Lee’s character defends underprivileged laborers against a corrupt boss. In his second film, Fist of Fury (1972) he takes on Japanese overlords in Shanghai. The film took an emotive stance against colonial racism and included Lee taking out a Caucasian villain. In his third film, Way of the Dragon (1972) Lee again fought for oppressed workers. At the climax, Lee’s character kills Chuck Norris’ in a duel that remains, to this day, one of the finest fights ever put on celluloid.

- Bruce Lee versus Chuck Norris in Way of the Dragon. Video: YouTube

Audiences around the world loved it; Asian martial arts boomed globally. But there were deeper reasons for Lee’s popularity than simply his spectacular combative prowess – reasons that had much to do with the socio-political developments of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s.

The United States was embroiled in its first-ever losing war, battling Asian peasants in Vietnam. The conflict’s horrors and moral conundrums were beamed directly into US living rooms on the evening news. A new mistrust was rising toward Washington, and a counter-culture was questioning previously held white, paternalistic values and beliefs.

From star to legend

“The reason Lee has this hold on the world is he presented a very different vision of non-white masculinity at the height of the Vietnam War,” Gina Marchetti, a professor of comparative literature who specializes in film at the University of Hong Kong told Asia Times. “People were already rethinking the white male hero, the John Wayne hero… Lee created a figure who could draw you into action-adventure and could speak in audible ways to anti-colonial and anti-racist sentiment.”

Moreover, Lee embodied a positive new self-identity for Asian males who had previously suffered from both under-representation and misrepresentation in Western cinema – as devious villains or emasculated wimps, often played by white actors in “yellowface.”

“Bruce Lee was the tipping point,” said Michael Hurt, a Social Science Korea Research Professor at the Center for Glocal Culture and Social Empathy at the University of Seoul. “The representation shifted from passive sexless to a kind of hyper-masculine manly mode. Ask any Asia-American: Bruce represented an important shift in Asia maleness.”

Watching the box office receipts Lee’s films were garnering around the world, and perhaps recognizing the paradigm shift underway, Hollywood came calling. The result was the Golden Harvest-Warner Bros co-production Enter the Dragon (1973). Marrying Hollywood production values, a Hong Kong location and a multiracial cast with Lee’s talents, it would become a worldwide blockbuster.

However, by the time it hit screens, Lee was dead, the victim of cerebral edema. The world was stunned.

Still, Lee’s shock, early death enshrined him in legend. Lee joined a triumvirate – made up of himself, Jamaican reggae sensation Bob Marley and Argentinian rebel Che Guevara – of global pop-culture icons who did not hail from the prosperous, white West. To this day, the Asian, the Black and the Latino are instantly recognizable, adorning posters, t-shirts and other designs on every continent.

It is Lee’s status as one of the first non-white stars that has generated such heated criticism of Tarantino.

Tarantino and Trumpism

Shannon Lee, the late Lee’s daughter and caretaker of his estate has led the charge. In interviews with US media, she has told Tarantino to “shut up,” criticized the director’s knowledge of her father and suggested he apologize. And she has a powerful ally in the form of ex-basketball superstar and African-American icon Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

“Tarantino has the artistic right to portray Bruce any way he wants,” wrote Abdul-Jabbar in a column in Hollywood Reporter. “But to do so in such a sloppy and somewhat racist way is a failure both as an artist and as a human being.”

Abdul-Jabbar, who studied kung fu with Lee and appeared as the towering villain in Lee’s last, unfinished film Game of Death, took particular offense at the way Lee is handled by a white American character in the film.

“The John Wayne machismo attitude of Cliff (Brad Pitt), an aging stuntman who defeats the arrogant, uppity Chinese guy harks back to the very stereotypes Bruce was trying to dismantle,” Abdul-Jabbar wrote. “Of course the blond, white beefcake American can beat your fancy Asian chopsocky dude because that foreign crap doesn’t fly here.”

Experts back Lee and Abdul-Jabbar.

Frances Gateward, an expert on Asian film at California State University, calls Tarantino’s Brue Lee an “abhorrent and disrespectful representation.”

“The film, through its narrative and aesthetic, is read by many critics and scholars as a film that celebrates the identity politics of the era presented – that it is a nostalgic celebration of the era of the last gasp of the white patriarchy,” she told Asia Times.

Making the film’s treatment of Lee doubly surprising is Tarantino’s previous role as a champion of non-Hollywood genres. In his prior work, he has paid homage to blacksploitation (Jackie Brown, 1977, kung fu (Kill Bill, 2004) and spaghetti westerns (Django, 2012).

Is Tarantino’s latest flick an ironic jab at the old “stale-pale-male” Hollywood? Experts are baffled.

“I don’t know Tarantino, but I do see a change in his attitude toward Hong Kong cinema between Kill Bill and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood,” said Marchetti, who pointed out that the director dressed Uma Thurman’s character in Kill Bill in Bruce Lee’s now-famous yellow-and-black tracksuit from Game of Death. “What it represents in terms of ‘Making America Great Again,’ I don’t know.”

Marchetti critiques Tarantino’s film more widely as a failure to portray the 1960s as an era of civil rights, of the anti-war movement and of the emergence of youth culture. “This is an old man’s movie!” she said. “It looks very deliberate as, 50 years later, we are in a time of backlash. a time of the ascendancy of Trump.”